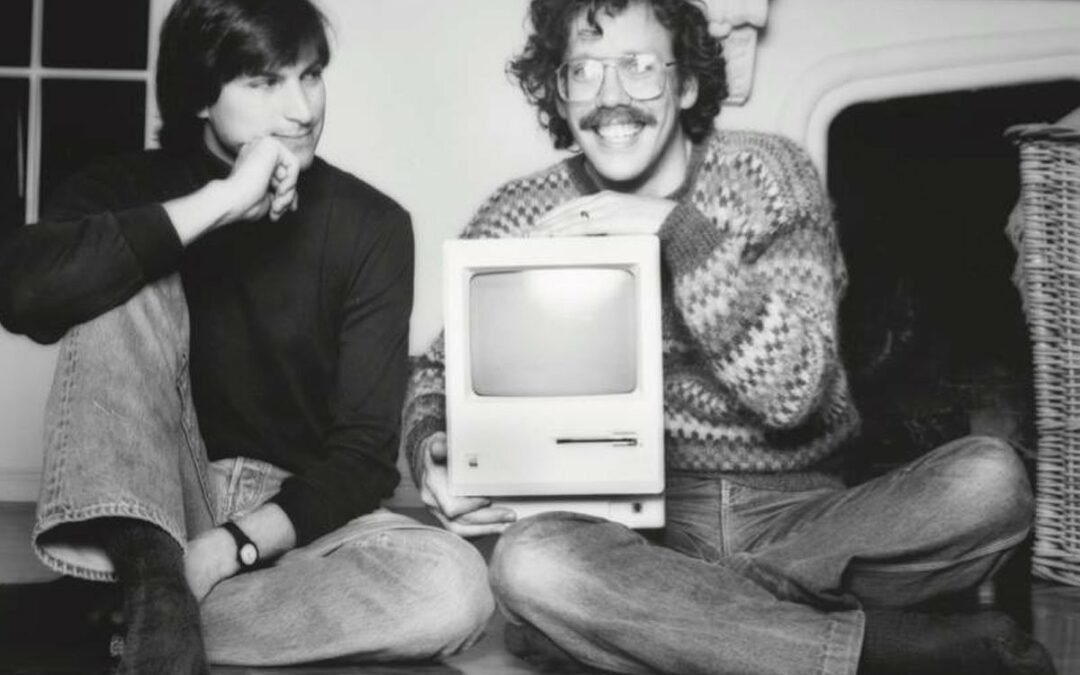

I will never forget my first encounter with Bill Atkinson. In November 1983, while working for Rolling Stone, I was able to visit the group developing the Macintosh computer, which was set to be released early the next year.

“Wait till you meet Bill and Andy,” everyone would say to me, referring to Atkinson and Andy Hertzfeld, two important developers of the Mac’s software. I wrote the following about the experience in my book, Insanely Great:

First, I met Bill Atkinson. In one of his roles as an unhinged Vietnam veteran, he had the disconcerting intensity of Bruce Dern. He was a towering man with flaming blue eyes, wild hair, and a Pancho Villa mustache. He was dressed in jeans and a T-shirt, much like everyone else in the room. He asked me if I wanted to see a bug. Pointing to his Macintosh, he dragged me into his cubicle. An extremely realistic drawing of an insect filled the screen. It was stunning, something you wouldn’t see on a home computer but rather on a high-end workstation in a research center. After laughing at his joke, Atkinson became very serious and spoke in a deep, almost whispery voice that gave his comments a respectful tone. He declared, “There is no longer a barrier between words and pictures.” “The art world has been a holy club up until now. similar to excellent china. It is now used on a daily basis.

READ MORE: Apple Releases iOS 26 With The Redesigned Liquid Glass

Atkinson was correct. He had told me in a whisper at the Apple headquarters known as Bandley 3 that day that his contributions to the Macintosh were essential to that breakthrough. He would go on to make another significant contribution on his own a few years later with a program called Hypercard that foreshadowed the World Wide Web. He maintained his enthusiasm and joie de vivre throughout it all, and he became a role model for anyone who wanted to use code to change the world. After a protracted illness, he passed away on June 5, 2025. He was seventy-four.

Atkinson had no intention of being a personal computer pioneer. He attended the University of Washington as a graduate student, where he studied neuroscience and computer science. However, he fell in love with an Apple II in 1977 and joined the firm that made it a year later. His number was 51. He was one of the few people Steve Jobs took to the Xerox PARC research facility in 1979, and he was astounded by the visual user interface he saw there. Working on Apple’s Lisa project, it became his responsibility to translate that cutting-edge technology for the general public. He also created many of the modern computer conventions that are still in use today, such as menu bars. In addition, Atkinson developed QuickDraw, a revolutionary tool for quickly drawing objects on a screen. The “Round-Rect,” a box with rounded sides that would be a part of everyone’s computer experience, was one among those items. Before Jobs forced Atkinson to walk around the block and see all the traffic signs and other items with rounded corners, he had opposed the notion.

Jobs snatched Atkinson, whose work had already affected the Macintosh, the other Apple project based on PARC technology, when he took over the project. “Anything Bill Atkinson did, I took, and nothing else,” Hertzfeld, who oversaw the Mac interface, once told me when describing the Lisa features he had stolen for the Mac. After growing disillusioned with the Lisa’s exorbitant cost, Atkinson embraced the notion of a less expensive counterpart and started developing MacPaint, the application that would enable users to produce artwork on the Mac’s bit-mapped screen.

The crew started to disintegrate after the Mac launched. Atkinson was able to pursue his passion projects since he was an Apple Fellow. He started working on a device he named Magic Slate, which had a high-resolution screen, weighed less than a pound, and was operated by swipes on a touch screen and a pen. In essence, he was 25 years ahead of schedule in the design of the iPad. Atkinson hoped it would be so cheap that you could afford to lose six in a year and not be upset, but the technology wasn’t ready to produce something so powerful and little at such a low cost. He once told me, “I could taste Magic Slate, I wanted it so much.”

READ MORE: New Accessibility Features, Such As Future Support For Neural Implants, Are Announced By Apple

After Magic Slate failed, Atkinson was too depressed to switch on his computer and went into a months-long slump. He took LSD one night and left his house in the hills of Los Gatos. He decided to incorporate some of the Magic Slate concepts into Mac-compatible software after feeling rejuvenated by gazing into the enormous collections of pixels that comprised the night sky.

He created a program that would store data on virtual cards, including text, audio, and video. These would be connected to one another. This notion was reminiscent of a 1940s concept by physicist Vannevar Bush, which was refined by a technician named Ted Nelson, who dubbed the linking method “hypertext.” However, Atkinson was the one who made the software compatible with a widely used computer. Apple CEO John Sculley was astonished when he saw the application, which he called HyperCard, and asked Atkinson what he wanted from it. Atkinson declared, “I want it to ship.” Sculley consented to install it on each PC. As evidence of the success of the hyperlinking concept, HyperCard would go on to become a precursor to the World Wide Web.

In 1990, Atkinson departed from Apple. He soon joined a number of his fellow Mac team members, as well as future tech titans Tony Fadell (who would go on to help create the iPod) and Megan Smith (who would go on to become the CTO of the United States under Obama), to form General Magic, an ingenious attempt to create a portable gadget that essentially performed all of the functions of the iPhone fifteen years later. Regretfully, the business developed its product right before the internet became widely popular. It was too early again.

Atkinson developed a fascination for wildlife photography in his later years and created a number of breathtaking print collections. I have a collection of photographs he took of stones that had been sliced open and polished to a high sheen. The images taunted us with their mysteries, like organic, swirling fractal abstractions. His last appearance was at the January 2024 reunion of the 40-year Mac team. He participated in a happy panel with other Mac team members at the Computer History Museum while wearing his signature Hawaiian shirt, and he was just as vivacious as he had been the day I had met him.

Atkinson went to Burning Man in September of last year. He begged friends and well-wishers to pray for him after receiving a pancreatic cancer diagnosis on October 1, 2024, as he detailed in a Facebook post. He remarked, “I have already lived an incredible and wonderful life.” He released an updated version of his website earlier this year that allowed users to download his photos for free. He took a two-week sailing vacation to Puerto Rico and the British Virgin Islands as late as this year. With relatives by his side, he passed away in bed. His wife, two daughters, two stepchildren, and a dog named Poppy survive him. Bill is responsible for every link in this obituary.

Step into the ultimate entertainment experience with Radii+ ! Movies, TV series, exclusive interviews, live events, music, and more—stream anytime, anywhere. Download now on various devices including iPhone, Android, smart TVs, Apple TV, Fire Stick, and more!